We are delighted to share with you a two-part essay, Challenges And Opportunities for Artists Who Choose Enamel, by our intern Zhou Zoe Yuan, a fourth-year student at California College of the Arts. It is an excellent exploration of enamel’s place in the art world and a wonderful starting point for a discussion of these issues.

Challenges And Opportunities for Artists Who Choose Enamel, Part I

by Zhou Zoe Yuan

A Little History

Enameled vessel, 2360, by June Schwarcz, who began her enameling career in the 1950s. Collection of the Enamel Arts Foundation.

Enameling, the art of fusing glass to metal, is relatively invisible in the art world today. Such work is rarely sold in galleries or collected in museums, and the techniques are not taught in art schools. And yet enameling was once considered an important contemporary art form, whose vast potential was explored by some of our country’s most exciting artists. What happened, and what can we do to restore enamel’s standing as a legitimate art medium?

Enameling first became noticed in the U.S. at the beginning of the twentieth century, as one of the decorative arts that was popular during the Arts and Crafts Movement. Embraced by artists, and championed by curators and museum directors, enameling became a respected art form by the 1930s, and enjoyed a heyday through the 1950s. Enameled artwork was shown in museums and galleries and widely collected.[1] Then, with the development of small tabletop kilns, enameling began to be marketed as a hobby craft. By the 1960s, it had exploded in popularity and was widely used as a production method for simple jewelry and objects using pre-cut forms.

Karl Drerup, plate (Fishermen), 1940s. Enamel on copper. 1 1/4 x 7 1/4 in. Collection of the Enamel Arts Foundation.

As Bernard Jazzar and Harold Nelson noted in Painting With Fire: Masters of Enameling in America, 1930-1980, enameling’s broad popularity as an easy craft “began to undermine its status as a legitimate and highly regarded form of contemporary art.” This kept many serious artists from pursuing enameling as a professional career.[2] Having lost its footing in the art world, enameling has struggled to regain its identity.

Enamel eventually found itself being taught as a part of metalworking programs, as the ubiquity of “shake and bake,” or craft, enameling led to a backlash against using pre-cut forms, notes Judy Stone, founder of the Center for Enamel Art. Those who wanted to enamel on metal were obligated to learn to work with metal first as enameling ceased to be taught as a stand-alone medium. At the same time, cloisonné jewelry was enjoying a resurgence in the marketplace, and demand rose for classes in cloisonné (a small-scale, delicate technique used mainly in jewelry).

Together, these shifts secured enameling’s place in jewelry and metalworking programs, where it has remained, almost completely, ever since. As Stone has suggested, the emphasis on metalsmithing in the enameling process began to alienate artists who had been working on a larger scale, on pre-formed flat or almost flat panels. These artists may have felt unappreciated in metalworking classes, or were simply not interested in those techniques. They gradually drifted away from enameling as a means of expression, which further eroded enamel’s standing as an art form.

Today, enameling is known primarily as a metalworking technique, as one of the many ways to color metal. But enamel is special for more than its permanent, vibrant color. As James Doran noted in his keynote speech, “Artists Who Choose Enamel,” at the Enamelist Society Conference, “Great Expectations,” in 1995:

“It [enamel] can be worked in two dimensions like paint and canvas, it can have form and dimension like any sculptural material, it can have at least the durability of clay, it can have the optical depth of glass (after all, it is glass) and it has a flexibility of scale, from the very small wearable art to the very large architectural installation.” [3]

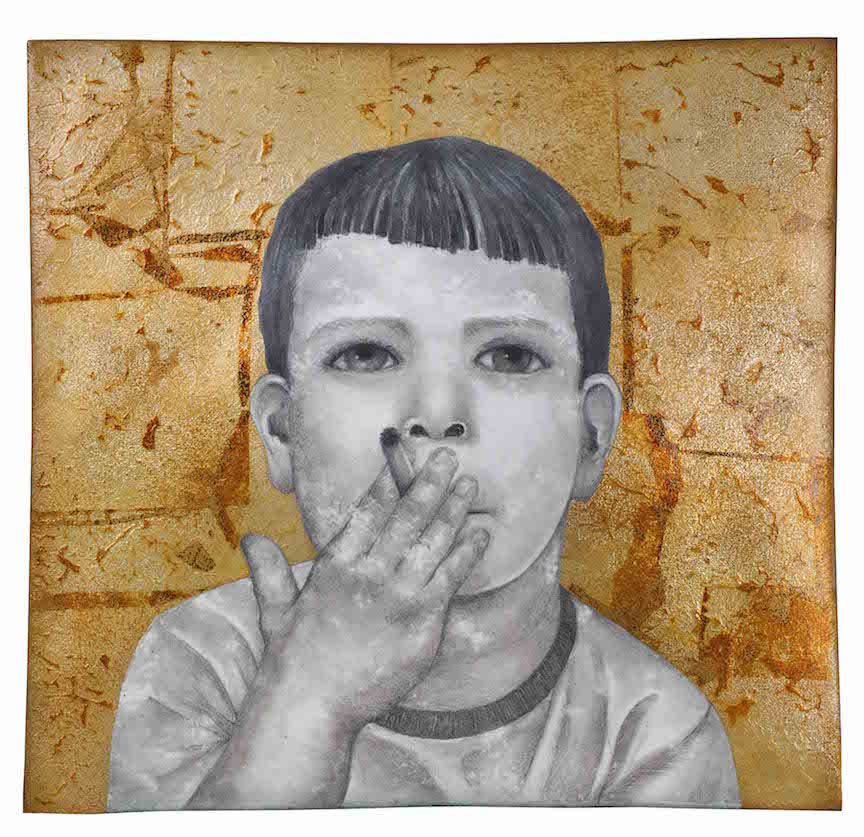

Jessica Calderwood, Smoking Boy, enamel, copper, silver foil, 12″ x 12″ x 1″, 2005. Collection of the Enamel Arts Foundation.

A true art medium, enameling has its own unique process, technique, vocabulary and craft. It is special, yet it is not exclusive. As Doran indicates, enameling is accessible to, and useful for, any artist, whether painter, sculptor, metalsmith, jeweler, glass blower, photographer, printmaker, or ceramic artist. On the strength of its potential alone, enamel’s future as a fundamental artistic tool should be assured. In reality, we have a long way to go.

Enameling Education

In the 21st century, enamelists are still “a rare breed.”[4] Enameling is given little attention by academic institutions and museums, books on the subject are few, and suppliers are fewer still. One of the biggest challenges for aspiring enamelists is how to learn the techniques. Currently there is no independent degree program for enameling in the U.S. Budget concerns, as well as the prevailing taxonomy, cause colleges to routinely merge enameling into jewelry and metal programs.[5] But this system potentially limits enameled work to small formats, and makes it hard for artists to consider using the medium to paint, draw, photograph, silkscreen, or create larger sculptures.

Outside of academia, a few programs have sprung up with classes that allow students to work larger and more experimentally, from rendering on steel to enameling on three-dimensional forms. Because these workshops are offered independently, they can be quite innovative and cutting-edge, with a sense of mission about their curricula.

Jan Harrell and a student examine a large piece at a Radical Enameling workshop at the Center for Enamel Arts.

For example, the Radical Enameling Workshop series in the Bay Area, offered by the Center for Enamel Art, focuses on the use of unusual materials and techniques. In addition to broadening the parameters of contemporary enameling, its goal is also to expand the critical conversation about enameling as an art form. Judy Stone, who created the series, has encouraged enamelists and enamel instructors in academia to build collaborative relationships with other fine-art instructors, to show that enameling can used by those who want to render (painters, drawers, printmakers), work with images (photography, silk screen), or incorporate enamel into three-dimensional sculptural forms.

Workshops like these are still relatively rare because they require substantial resources to make them happen: space, equipment, and organizational skills. They are, however, very popular among aspiring enamelists. They also provide exciting opportunities and challenges for instructors. Many are taught by college professors who have been enameling for decades, but who may have limited choices for professional development; some are taught by recent college graduates who have few teaching opportunities and have been experimenting with new technologies that they have adapted for enameling. Teaching a workshop like this gives instructors experience and credentials that are highly valued in the community.

NEXT WEEK:

Part II: What Is Missing From This Picture?

About the author

It has been a wonderful journey for me since I set foot in the enameling world a year and a half ago. Learning to enamel is laborious, but never tedious. It requires patience and practice to understand the characteristics of the medium, and to control it and make it work for me! In addition to my practice I wanted to know more about enameling, its history and status quo in the U.S. I discovered that for artists who choose enamel there are great challenges, but also remarkable possibilities. Here, I share my observations and insights with each one of you who believes in the future of this medium. Thank you for joining me, and welcome!

It has been a wonderful journey for me since I set foot in the enameling world a year and a half ago. Learning to enamel is laborious, but never tedious. It requires patience and practice to understand the characteristics of the medium, and to control it and make it work for me! In addition to my practice I wanted to know more about enameling, its history and status quo in the U.S. I discovered that for artists who choose enamel there are great challenges, but also remarkable possibilities. Here, I share my observations and insights with each one of you who believes in the future of this medium. Thank you for joining me, and welcome!

—Zhou Zoe Yuan

Footnotes

[1] Bernard N. Jazaar and Harold B. Nelson. Painting with Fire: Masters of Enameling in America, 1930-1980. (Long Beach Museum of Art, 2006), 15.

[2] Jazaar, and Harold B. Nelson, 181.

[3] James Doran. “Artists Who Choose Enamel.” Glass on Metal. December, 1995, 132.

[4] Doran, 131.

[5] Gretchen Goss and Maria Phillips. “Enamel: A Current Perspective”. Sculptural Object Functional Art and Design. http://www.sofaexpo.com/chicago/essays/2003/enamel-a-current-perspective.

Recent Comments