Coral Shaffer and her one-woman business, Enamelwork Supply, are an essential part of the enameling community today, supplying artists and production enamelists worldwide with hard-to-find enamels, tools, and expert advice. In this illuminating interview, part of our Tools and Supplies series, she speaks at length about the pleasures and challenges of selling enamels, and why Japanese enamels, renowned for their color and clarity, are becoming an endangered species. We are deeply grateful to Coral Shaffer for the services she provides, and for sharing so much with us about her work.

Coral Shaffer at a trade show selling her pieces

CEA: You started out as a production enamelist in the 1970s. How did you get into that work?

CS: I fell into it by accident. My original business partners, Pat and Judy Strosahl, were friends of mine, and I was living with them when someone loaned them a kiln. We started experimenting for fun. None of us had even had an art class, let alone an enameling class. I was a teacher originally. Then I worked as a house mother for developmentally disabled kids, and then I worked at a bakery. At one point Pat and Judy and I all worked for Judy’s brother, who owned a tropical fish store.

Coral’s booth at a show

At first we just made enameled gifts for family. But friends suggested that we try to sell them. Well, that was a novel idea! We started at street fairs, and the next thing we knew, the pieces sold. We moved to galleries and the pieces sold. We moved to catalogs and the pieces sold.

CEA: Making things by hand, as well as as living “off the grid,” with nontraditional income streams–those were certainly popular at the time. Did you see yourself as a part of that movement?

CS: Absolutely. We were in the middle of an era. Every other house in Seattle, it seemed, had someone who was crafting. A lot of our friends did something along those lines. Pat’s father, Judy’s mother and my father all had their own businesses. It just seemed very natural for us to do the same.

CEA: Enamelwork Supply grew out of the production business, when you began selling the enamels you were importing for your own work.

CS: At first we imported just for ourselves. But then we thought we might as well be selling to other people as well. Then, when my partners eventually left for other jobs–they had three kids to put through college–I found I could not do both the enamel retailing and the production work by myself. I did have a small line of pieces that I made for a while, but as the supply part of the business got busier I stopped doing that too. I chose to continue the importing part of the business because I had a relationship with the Ninomiyas, the family that produced the enamels I imported from Japan.

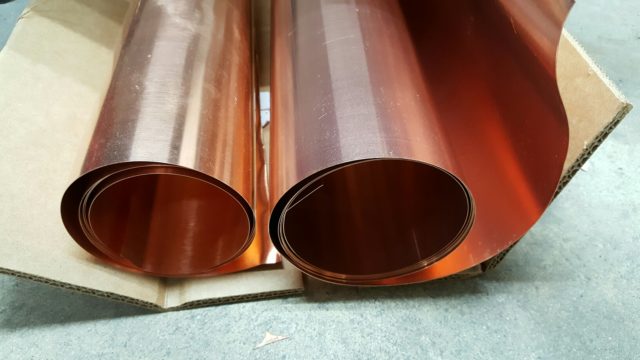

Wet-packing enamels for production pieces

CEA: Is importing more of a moneymaker for you than the production work was?

CS: It’s hard to say. There are ups and downs in both income streams. There is no big moneymaker. Rarely does anyone get rich in the area of enameling–from making the raw enamels to making the finished pieces. You have to really want to do it.

CEA: Let’s talk about lead-bearing enamels for a moment. Producing them domestically has become prohibitively expensive because the environmental regulations are so strict, but a few small overseas companies still make them. You have long relationships with some of these companies, and Enamelwork Supply has become one of the most important distributors worldwide. How did you come to specialize in these enamels?

CS: When United States companies stopped making lead-bearing enamels, my partners and I still wanted to be able to use them. So we began importing Schauer enamels, when they were still being made in Austria. Later, in the 80’s, I studied enameling in Japan and when I returned to the U.S. I began importing Japanese lead-bearing enamels.

Lead-bearing enamels are getting harder and harder to find. You can get them from England, you can get them from France, and you can get them from Japan. Other companies that make them don’t export; they make them for themselves, as far as I know.

Enamels by the kilo in Coral’s studio

CEA: If you were explaining to a novice why lead-bearing enamels are superior to unleaded, what would you say?

CS: First, I think lead-bearing enamels, at least the transparents on copper, are easier to work with. One of the things the lead does is help the enamel melt. If you are working with copper, there is a red oxide that forms. If you don’t fire long and hot enough for the enamel to get sufficiently molten, it won’t suck that red oxide up, and your transparents, particularly the lighter ones, are going to be the color of tomato soup. With a Thompson enamel–at least, this happens to me–the edges turn black before the oxide disappears. And that doesn’t happen as readily with the lead-bearing enamels.

I also think lead-bearing enamels, particularly the transparents, are prettier. It’s difficult to explain. There are more color options and the colors are more brilliant. I’ve heard it explained as the difference between window glass and lead crystal. There is something about lead-bearing enamel that reflects, or refracts, the light differently.

However, this is the opinion of someone who has a vested interest in selling lead-bearing enamels. I advise people to get Thompson Enamel’s perspective on this.

CEA: I see that on your site, in addition to supplies and books, you offer “help from an experienced enamelist by phone or email.” Is providing technical assistance a big part of your job?

CS: Yes. Sometimes people want me to teach them everything about enameling over the phone, and that is too hard to do. But if people have specific questions or something happens they can’t understand, then trying to help is a fun part of my job. I would hate it if people stopped enameling because they thought, “I’m just too dumb.” Chances are it is not them, it is the material.

Coral’s newest book, available on her site.

CEA: Are there others like you who are selling in the U.S. now?

CS: Thompson is the only big supplier. The rest of us are all small or at least the enamel selling part of the business is small. Most people who sell enamels are buying from Thompson and selling their brand of enamels. A lot of the Thompson distributors are one-person operations. I’m always amazed at the people who call me and say, “Are there any suppliers closer to me? I’m in Timbuktu.” And I say, “Do you realize there are just a handful of us in all the United States? You’re probably not going to find an enamel store on your block.” It’s not precious metal clay, it’s not painted rocks. It’s nothing that people have been interested in doing en masse, unfortunately.

I am able to make a living because I live very simply, and because my studio is in my house and because I have a website. If I had had a storefront I’d have been gone long ago. I am lucky to get orders from all over the US and from overseas too, due to my presence on the web.

“I would hate it if people stopped enameling because they thought, ‘I’m just too dumb.’ Chances are it is not them, it is the material.”

CEA: Your relationships with the Japanese enamel makers are particularly valuable for artists and companies that depend on these enamels but don’t speak the Japanese necessary to buy directly from them.

CS: Some of the watchmakers in Switzerland are my clients because they like the Japanese enamels and they can’t find anyone else who speaks English who sells them. That is true of English speaking customers in other parts of the world also. I know a little Japanese, though I still sit here with my dictionary when I need to communicate with my suppliers. And it is not only the language; the suppliers only sell by the kilo, and not many enamelists need that much.

CEA: Did you ever think about expanding your business, having employees?

CS: Because of the paper work involved, I don’t think that it makes sense to have employees until you can have a number of them. I won’t ever get that big. Also, because of the “feast or famine” type of business that this is, I would not want to hire someone one month and lay them off the next. Besides, customers usually need to talk to me–an employee would not know how to answer questions.

CEA: You enjoy working for yourself.

CS: Office politics are something I don’t handle very well. This way, I only have issues with myself!

CEA: Is there anyone who could be your successor?

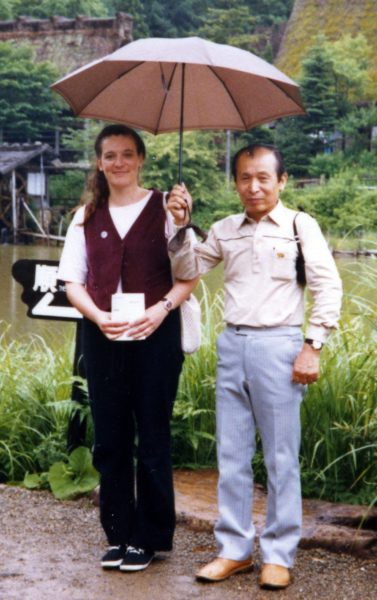

Coral with her enamel teacher in Japan, Mr. Okamoto

CS: Selling Japanese enamels is a niche of a niche. It’s a very specialized thing. Number one, you don’t make much money. Number two, you need to know a little Japanese, or have a translator on hand. Number three, although I could make introductions with a letter, it’s a good idea to meet the manufacturers in person. I’ve been over there several times and met with the whole Ninomiya family. It is a family business. And that is important to the Japanese. Number four, you also have to know how to enamel, and you have to know about these particular enamels in order to answer questions. So you have to be somebody very specialized. And I don’t know who that person is.

CEA: Would you consider training a successor?

CS: Possibly, but I would not want anyone else taking the Enamelwork Supply name. I could turn over Enamelwork Supply to XYZ company, but I’d be very upset if something unfortunate happened–like selling contaminated enamel or overcharging–when my business name was attached and it was out of my control.

But I will give people fair warning when I decide to quit. Once, I received a letter from Mr. Ninomiya that I interpreted as saying that he no longer would be making lead-bearing enamels but making lead-free enamels instead. It turned out not to be true. But I had already put the word out, and I had to retract it. It was pandemonium. I don’t want a panic like that to happen again. That’s why I would let customers know a year before I intended to retire.

CEA: Would any of your distributors be interested in picking up your business?

CS: I don’t have any distributors. And I do not know if any other enamel distributors in the US would be interested.

CEA: Obviously you are sort of a lifeline to many enamelists.

CS: Well, that may be overstating it! But I take my responsibility seriously, let me tell you. I’ve had sleepless nights wondering what I am going to do. I’m 73 now. At some point, I am going to transition out of this, particularly if I lose my studio because of high rent. I doubt I could find another place to rent where I could actually put my kiln in my house. For now, I’m just trying not to worry about it until something points me in a direction. I have faith that at some point, something will. Whatever happens, I consider myself to be extremely lucky. I’ve had 40 years of making a living at doing what I wanted to do.

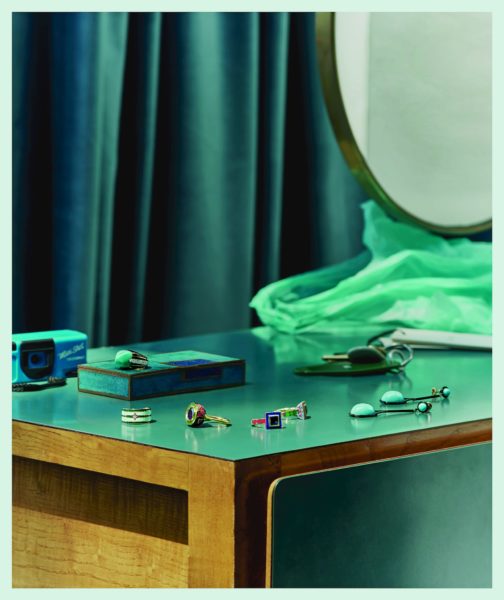

The photographs are pretty — still-lifes in dusty jewel-tones, the items scattered on shabby-chic dressing tables as though tossed there at the end of some fabulously debauched evening. Care has been taken with a whimsical mix of props –a bowl of candies, lipstick on a wine glass, vintage hotel keys. But the pieces themselves are lost in the scenery, an afterthought, the details and the colors almost too small to see. And those vintage aqua colored Belperron earrings, that pop so nicely on the page? They are made of turquoise and lacquer, says the website. Not enamel.

The photographs are pretty — still-lifes in dusty jewel-tones, the items scattered on shabby-chic dressing tables as though tossed there at the end of some fabulously debauched evening. Care has been taken with a whimsical mix of props –a bowl of candies, lipstick on a wine glass, vintage hotel keys. But the pieces themselves are lost in the scenery, an afterthought, the details and the colors almost too small to see. And those vintage aqua colored Belperron earrings, that pop so nicely on the page? They are made of turquoise and lacquer, says the website. Not enamel.

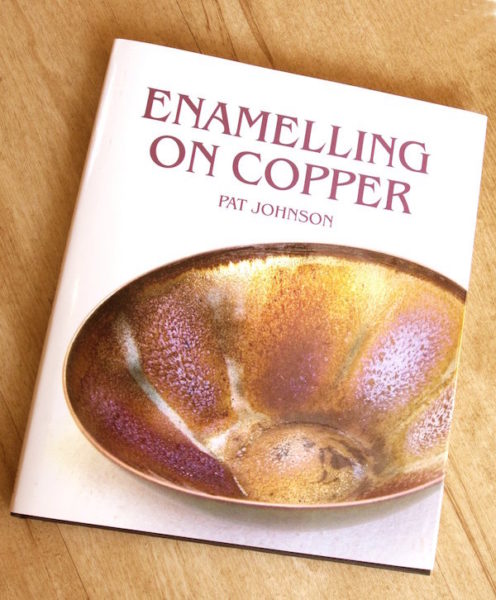

Enamelling on Copper by Pat Johnson

Enamelling on Copper by Pat Johnson