We are thrilled to introduce a series of guest posts by the enamel artist Kat Cole.

Cole, who has been making distinctive enameled steel jewelry, met Center for Enamel Art founder Judy Stone last year when Cole taught a Radical Enameling workshop for the Center. Stone encouraged Cole to explore the expanded use of industrial materials in her work, and connected her to KVO Industries, a partner of the Center for Enamel Art, where Cole created a large sculptural piece. Cole’s posts give insight into her practice and process as she brings a new scale to her work.

We will begin republishing her entries next week. Join us, and her, as she learns to think big!

A Little History

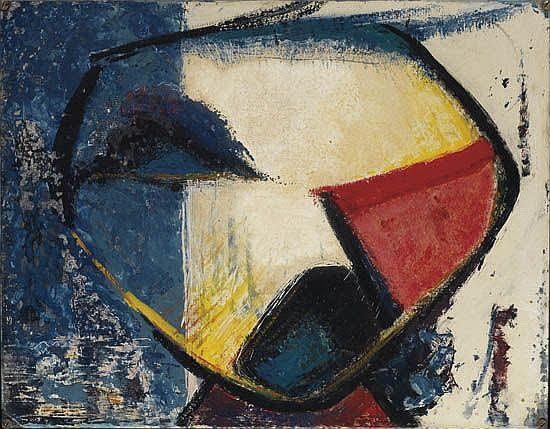

Edward Winter, “Mexico,” enamel, 1940. Cleveland Museum of Art

Enameling–technically defined as glass bonded to metal–can take many forms. Today the term is generally used to mean small, intensively crafted, jewel-like work, set into wearable or functional objects.

But in the not-so-distant past, enamelists commonly worked much larger, on art pieces the size of a painter’s oversized canvas. Some of this work was on copper, but quite a few enamelists were able to work on large steel panels. Why has large-scale enameling all but disappeared in the US, and how can we encourage its revival?

Enameled steel, Sargent Johnson, 1957

From the 1930s through the 60s, large-scale enameling was an important industry. Signs, appliances, and even architectural elements were enameled in giant industrial plants. Supported partly by government programs during the Great Depression, some artists were given broad access to these facilities, where they could produce large two-dimensional pieces on steel.

Enamelists like Edward Winter and Kay Whitcomb, and multi-media artists like Sargent Johnson created important works on enameled steel during this period. Johnson, a noted African American sculptor from the Bay Area, was the first commissioned artist of the new civic center in Richmond, CA, with his porcelain-enameled steel sign for the city, “American Pride and Purpose.”

Over the years, however, the enamel industry has grown smaller as less expensive materials have supplanted enameled steel. Artists today have virtually no access to enamel factories, though they can still get their artwork reproduced in enameled steel.

“American Pride and Purpose,” Sargent Johnson, commission for the city of Richmond, CA, ca. 1949

KVO is one of the few industrial firms in the US that is dedicated to working with artists directly, reproducing their art for commissions and inviting artists into the plant to work. Staff offer expert assistance to artists interested in working large, creating public installations and site-specific art, or who want to produce decorative or functional objects to sell. A pioneering program between the Center and KVO, introduced this spring, opens KVO’s facilities for designated “work days,” when anyone can come to the facility to learn about the enamel industry and “play” with the materials.

Enameled elevator doors, Kay Whitcomb, 1971

Partnerships like these are a win-win for artists and the enamel industry alike. Artists learn the latest technologies and can push the boundaries of the medium, and the enamel industry nurtures new demand for its products. Kat Cole is an important part of this relationship, and we look forward to her insights as she thinks expansively about the possibilities: how to re-connect artists to techniques and supplies and restore the relationship between artists and industrial enameling.

Recent Comments